Sealed reading room in the European Parliament for documents relating to the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) negotiations. The room was initially accessible to only a few Members of the European Parliament. Photo by Greensefa, CC BY 2.0.

Over the past couple of years, the European Union and the United States have been negotiating a new trade treaty behind closed doors. The Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) would arguably “liberalize one-third of global trade”—but we can’t be sure, because negotiations are kept secret. We are already familiar with the secretive nature of such processes thanks to our experience with the negotiations for a similar treaty called the Trans-Pacific Partnership. Trying to figure out what is going on with TTIP is like trying to figure out who likes whom at a teenager’s party—it takes gossip and guessing. The lack of information in the negotiation process, however, is not merely a result of ongoing tactics as negotiations heat up, it is planned. At a civil society dialogue meeting in 2013, a Directorate-General for Trade (DG Trade) official’s reply to a question on the Commission’s plans for more transparency was brief: “There will be leaks.”

In fact, leaks are a comfortable tool, not only for civil society and consultancies, but also for policy makers. It lets them share preselected information with the public without having to assume responsibility or comment on it. As any official will tell you: “The European Commission does not comment on leaks.”

What we know

We know the European Commission’s initial public position on intellectual property in TTIP. On copyright, DG Trade set three goals: 1) remuneration rights for performers, 2) public performance rights for authors and 3) resale rights for creators. The approach is one-sided, but at least we know about it.

In June 2015, the European Parliament has adopted a non-binding recommendation addressed to the European Commission, in which it included welcome passages in favour of data protection and against surveillance. However, the Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) remarkably refused to call for an exclusion of intellectual property rights (IPR) from the negotiations.

Sadly, not much else has been published or “leaked” so far. The logic of trade deals dictates that elements included in previous treaties will be proposed here as well. We thus need to be vigilant. From a free knowledge and digital rights perspective, this means that we have to look at the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and the Canada-EU Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA).

Free knowledge projects like Wikipedia couldn’t exist if their users could not easily share information and legally re-use content that is in the the public domain. Following the above described mechanism of international treaties, there are three aspects in TTIP we need to monitor carefully in the coming negotiations rounds:

- An additional right on temporary copies would have the potential to clash with the only currently harmonised exception in the EU and make technology harder to use and information harder to share.

- A trade treaty fixing the copyright term to lifelong plus 70 years would make it virtually impossible to revert the term lengths to at least the Berne Convention minimum of lifelong plus 50, thus permanently cementing the last contraction of the public domain.

- A further crackdown on technology circumventing digital rights management (DRM) would make it even harder to use and reuse knowledge, even where the use is clearly covered by a copyright exception.

These points are either part of TPP or the current CETA drafts. They are going to be proposed in the TTIP negotiations.

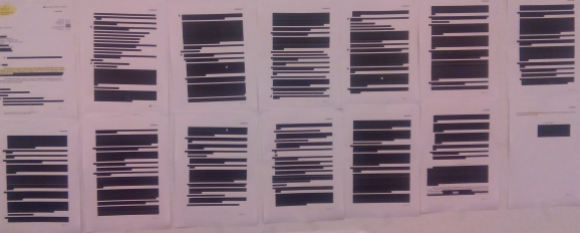

TTIP negotiation document released to the European Parliament. Photo by Dimitar Dimitrov, public domain/CC0.

Efficient negotiations and democratic legitimation

As in any international negotiation, there are two valid and conflicting demands. The people negotiating need to be able to do their job and this does include at times being allowed to speak off the record. On the other hand, in order for a treaty to be legitimate, the public needs to know what is being agreed upon and have enough time to reflect on it and to try to change the outcome.

So, negotiation logic dictates, as people involved will let you know, that a team’s goals and intermediate positioning are not known beforehand in order to not weaken its position. Another argument regularly put forward is that discrete talks are usually quicker and more effective. And while this is true, such strong secrecy as previously witnessed in the TPP negotiations and currently displayed in the TTIP processes seems short-sighted. It takes away some of the pressure in the room but builds it outside on the street. Outside pressure generates distrust, which is poison for public support and thus legitimacy.

In a decision by the Court of Justice of the EU, the judges weighed the public interest relating to the efficiency of decision-making against the public interest in openness. Albeit a different case, the judges ruled in favour of openness with the underlying belief that negotiation proposals “can be subjected to positive and negative comments by the public, and the risk that delegations would refrain from submitting written proposals does not sufficiently undermine the decision-making process to justify the refusal of access”.

The Logic of Leaks

Leaks might, at times, seem like a good patch to ease the tension between negotiating tactics and the need for legitimation. They do have huge drawbacks, though. They aren’t a legal concept and thus stand outside the democratic procedure. They are more often than not unreliable sources leading to confusing. Instead of creating trust and confidence they do quite the opposite. They quite often create distrust.

So far we have kept digital rights out of TTIP campaigns. But if information about the actual content of the treaty is shared only at a late stage of the process, fixing mistakes would be virtually impossible. This could put stakeholders in an all-or-nothing situation. Not exactly a great precondition for building wide support for an “ambitious trade deal”.

Dimitar Dimitrov, Project Lead

Free Knowledge Advocacy Group EU

Can you help us translate this article?

In order for this article to reach as many people as possible we would like your help. Can you translate this article to get the message out?

Start translation