Since July 2013, Dimitar Dimitrov is Wikimedian in Brussels. In assorted blog posts he talks about his experiences vis-à-vis the EU.

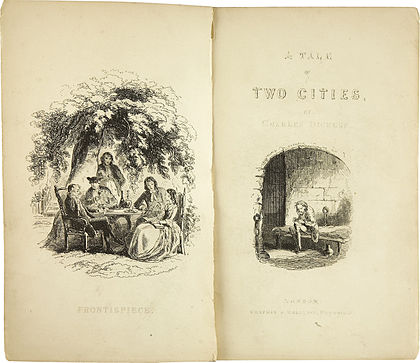

“Charles Dickens: A Tale of Two Cities. With Illustrations by H. K. Browne. London: Chapman and Hall, 1859. First edition. Photography Hablot Knight Browne, Heritage Auctions, Inc. Dallas, Texas. Public Domain

No, this title is not an original. It is largely copied. A derivative work that is legally unproblematic only because Mr. Dickens has been dead long enough. If I were to remix something newer, let’s say if I came up with “Pirates in the Copyright: Disney’s Chest” and included a picture and quotes from that particular work, well, that might get me into all kinds of trouble.

But copyright term lengths and how we deal with remixed content are just two of the fundamental questions we can no longer postpone. Information technology allows for sharing at virtually no cost. That is the positive promise the digital revolution has brought about. We must admit that this is a genuinely good thing and an opportunity for sustainable global development and improvement of people’s lives.

The other tale is more ambiguous. It retells the old story that every revolution brings about a new culture and new economy, but also puts out of business those who cannot adopt.

Position paper on EU Copyright Reform

The Wikimedia movement has read these two tales. We’ve suffered them, we’ve enjoyed them. We’ve experienced the practicalities, patches and peculiarities. We’ve thought, debated and worked with and around these issues for more than a decade now.

Recently, the European Wikimedia Chapters, together with a group of 18 further civil society organisations, published a Position Paper initially drafted by our EU Policy work group to be send to European Commission units responsible for intellectual property. We made four proposals that we’re convinced must be included in any meaningful copyright reform if it is to make anything fit the so-called “digital age”. These four points have one thing in common: they would drastically increase the commons and our ability to share content while leaving economic interests and thus financial profits virtually untouched. These four changes are:

- Harmonising copyright legislation, thereby making rules clearly understandable and reducing current legal risk

- Enshrining a universal Freedom of Panorama exception guaranteeing the right to use and re-use images taken in public spaces

- Clearly stating that publicly funded content must be public domain

- Growing the public domain by reducing copyright terms by 20 years (i.e. to the length set out in the currently binding international treaties)

Meanwhile in Brussels…

Even the new European Commission seems to have drawn the political conclusions from realising the inevitability of changing rules that were made with paper presses and horse-drawn carriages in mind. We are hearing that writing an actual reform proposal will take anything from 6-18 months in Brussels. This means that they’re hurrying which can only be interpreted as political pressure, at least for the moment.

After years of postponing tough decisions, the new President of the European Commission, who put copyright reform in his list of top priorities, moved the dossier and unit responsible for it to another directorate. It will no longer fall under the responsibility of the “internal market” (DG Markt), but is now housed by the Directorate-General responsible for the Digital Economy and Society and its Commissioner, the German Günther Oettinger. Overseeing Oettinger’s work will be Vice-President of the Commission Andrus Ansip from Estonia. His role is dedicated to establishing a “digital single market”, which can only mean harmonisation, which in turn is hardly possible without reforming copyright. The new composition of the European Commission and a recent Twitter hearing the Vice-President agreed to participate in give rise to some reasonable expectations that change might indeed be coming.

“Then tell Wind and Fire where to stop, but don’t tell me.”

Opponents of a copyright reform (which include, but are not limited to, publishers) are in fact not against the four points outlined above. The legal re-balancing we are proposing wouldn’t hurt the industry. They are simply against any change whatsoever, out of fear that it might be slippery slope to abolishing copyright. And while it isn’t a real intellectual challenge to argue that lack of change is much more likely to eventually kill copyright, rather than a few sensible updates, this “I will block anything that comes my way” attitude might turn out to be poisonous for reform. The only things law-makers shy away from more than bad law are unsuccessful legislative proposals.

It takes really strong-minded, shrewd and resolute politicians aided by a dedicated civil society to make things happen.

Tell them!

The good news is: optimism should derive from the fact that you can be part of that dedicated civil society that pushes its policy-makers to be resolute.

Wikimedians are working on being represented at the EU level to be part of the conversation when decisions about us and our daily work are made. By providing volunteers and supporters with necessary background knowledge, personal support and infrastructure, we’re trying to involve you in our advocacy activities!

If you prefer starting off solo, you can try contacting one of our European representatives from your region or country and warning them that a copyright reform is coming their way in about a year, while counselling them about digital culture and intellectual property. They are likely to be very busy people who have a hard time keeping track of every issues headed their way 😉

If you are a team player, please don’t hesitate to contact the coordinator from your country (and/or the Brussels project lead) to figure out what you can do together.

Alone or as an organisation you can follow Wikimedia UK’s example and snail mail decision-makers. Their response rate was impressive and snail mails are becoming less common today, showing that you’re willing to make that little bit of extra effort to gain their attention.

If you are not from or living in Europe, but you wish to engage in advocacy activities, there’s plenty to do globally. Please drop us a line and we will find a way to help each other!

Let’s lobby!

Dimitar Dimitrov, Wikimedian

Can you help us translate this article?

In order for this article to reach as many people as possible we would like your help. Can you translate this article to get the message out?

Start translation