Last month, the United States Copyright Office held seven discussion sessions focused on section 512 of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA)—the “safe harbor” from copyright liability provision in US law that allows entities like Google and Wikimedia to operate.

The Wikimedia Foundation, one of only two non-profit platforms in attendance, argued that changing the current law would interfere with Wikimedia sites’ volunteer-driven and effective handling of copyright issues. Section 512 is an integral part of these sites’ continued existence.

These sessions were organized as part of a years-long effort by the United States Copyright Office and members of the US Congress to write the “The Next Great Copyright Act.” As part of those efforts, the Copyright Office has been looking into the section of US law that protects online platforms from being liable when their users upload files that infringe copyright. Section 512 of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) creates these “safe harbors” as well as a notice-and-takedown process for rightsholders to request that platforms remove infringement.

Because Wikimedia benefits from these safe harbors and complies with the notice-and-takedown process, we’ve already submitted comments on the section to the Copyright Office, and last month I attended roundtable discussions on the topic as a representative from the Wikimedia Foundation’s legal team.

On May 12 and 13 in San Francisco, the Copyright Office organized seven section 512 discussion sessions, each with 20 participants. The topics of each session, which are listed in the roundtable agenda along with the participants, included the effectiveness and burdens of the notice-and-takedown process, the role of fair use, automated systems for sending and processing notices, repeat infringer policies, voluntary enforcement agreements between platforms and rightsholders, and misuse of the process.

Throughout the sessions, Wikimedia served as an example of how the current copyright enforcement system works for organizations that are neither tech giants nor for-profit rightsholders. We and Internet Archive were the only two non-profit online platforms who sent representatives to the discussions. On the Wikimedia projects, particularly Wikimedia Commons, the DMCA’s notice-and-takedown process plays only a small role in preventing copyright infringement. The community members who voluntarily enforce project policies do the heavy lifting by removing files that infringe copyright. As a result, we receive very few valid takedown notices—only 12 in all of 2015.

The numbers show that Wikimedia’s current systems work well to keep copyright infringement off the projects. Most of the time, volunteers take care of copyright issues before rightsholders even notice them—Wikimedia communities attention to copyright details mean that they regularly perform complex analysis to determine if files are allowed on the projects. When something does stick around long enough, the notice-and-takedown process is an effective backstop. This system can exist because of the current legal regime—but as I argued to the Copyright Office, changing the law could interfere with this system.

In our view, it’s not necessary to burden online platforms further in an attempt to curb copyright infringement. The rightsholder representatives at the roundtable pushed for a requirement that platforms implement filtering systems (also called “notice-and-stay-down”). Once a file has been removed in response to a takedown notice, these systems would automatically prevent users from uploading the file again.

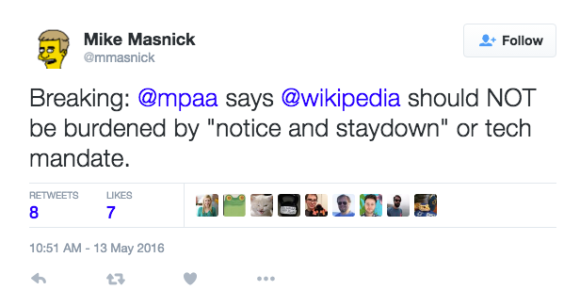

However, it is costly to implement such systems well—and it would be exceptionally hard on nonprofits like us. First, the variety of content and file types hosted on the Wikimedia projects makes it an incredibly difficult technological challenge to build such a tool that both works effectively and doesn’t over-remove files and chill speech. Second, being forced to monitor for infringement ourselves would reduce the Wikimedia communities’ ability to govern the projects. While we did not convince rightsholders to abandon their campaign for requiring filtering, we did convince some that such a requirement should at least not apply to Wikimedia:

In my statements I also tried to remind the Copyright Office of how section 512 fits into broader copyright law. I pointed out how statutory damages—up to $150,000 for a single case of copyright infringement—create strong incentives for platforms to strictly comply with the notice-and-takedown process. Since any mistake in leaving up files that infringe copyright could cost tens of thousands of dollars, the section 512 safe harbors are crucial for platforms’ continued existence.

The fundamental purpose of copyright law is not to benefit authors but to ensure the public is able to enjoy new creative works. It is therefore important to ensure that the voices of the public and public interest are represented in these discussions.

We do our best to give Wikimedians a voice, advocating for the public’s ability to share knowledge and remix creative works, but the Copyright Office would benefit from hearing from you directly.

They will be requesting another round of comments on section 512. We will contribute, and we encourage you to do so as well.

Further reading:

- The Copyright Office page for their section 512 study.

- Techdirt’s overview of the arguments rightsholders made at the roundtable.

- Professor Rebecca Tushnet’s notes from the separate New York roundtable (the Copyright Office held the same discussions in both New York and California).

Charles M. Roslof, Legal Counsel

Wikimedia Foundation

Can you help us translate this article?

In order for this article to reach as many people as possible we would like your help. Can you translate this article to get the message out?

Start translation